The Role of Narrative in Legitimising Violence

- Dr Stephen Anning

- Oct 20, 2025

- 8 min read

Introductions

People are driven by narrative because narrative provides a way to rationalise the world. Hostile narratives tell stories as old as human history; hostile narratives are stories of heroes facing off against villains to save humanity. Analysing these narratives reveals powerful insights into how societies shape identities, beliefs, and actions. They act as interpretative frameworks through which individuals and groups understand lived experiences and the broader world. As explained here, people use hostile narratives to legitimise violence by creating social conditions where aggression towards target groups - whether imagined or real - is justified.

This explanation of narrative analysis illustrates the need to integrate qualitative research approaches into operational systems for intelligence analysis. The qualitative aspect of narrative analysis involves using story analysis techniques to uncover insights about people from the stories they tell themselves. These insights provide a more contextual and nuanced approach beyond the purely quantitative approach to modelling language that dominates natural language processing.

What Is a Narrative?

A narrative is a structured story that people or groups use to make sense of events, experiences, and moral outlooks. As Akinsanya and Bach (2014) observe, “A narrative is a story that contains a sequence of events that take place over a time period… it mostly follows a chronological order and usually contains a link to the present in the form of a lesson learnt by the narrator… narrative analysis seeks to find the link by analysing and evaluating various parts of the narrative.” Narratives help individuals to rationalise life experiences into coherent sequences with identifiable characters, conflicts, and resolutions (Polkinghorne, 1988; Riessman, 2008). More than just a means of transmitting information, narratives shape identities, influence behaviour, and foster social unity by forming moral frameworks for interpreting reality.

How Do Narratives Feature in Formulating Identity?

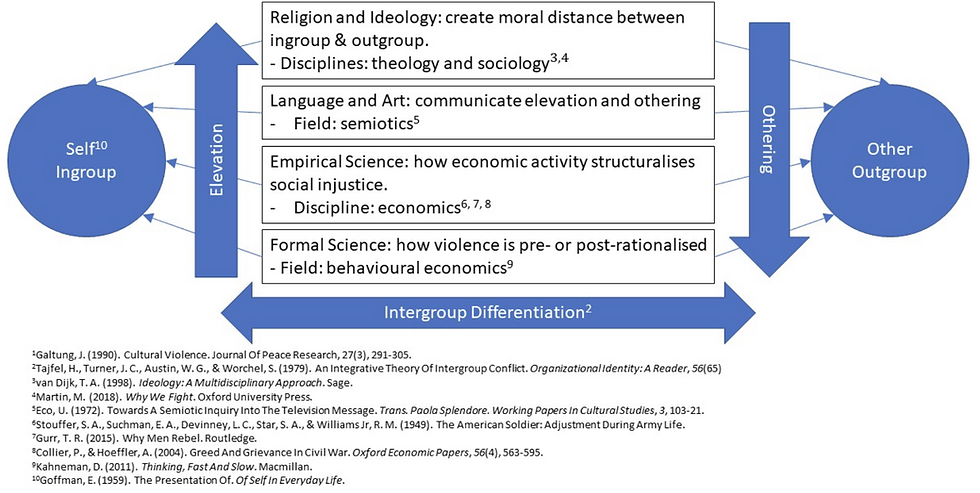

Narratives are central to shaping both personal and group identities. Social Identity Theory posits that people often define themselves through group memberships, with narratives reinforcing identity boundaries between the “Self” (ingroup) and the “Other” (outgroup) (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Shared narratives enable groups to build collective memories, sustaining core values and norms (Wertsch, 2002; Berger & Luckmann, 1966). Such stories frequently establish moral codes that guide behaviour, thereby bolstering social cohesion and a sense of belonging. According to van Dijk (1998), narratives serve as a “social database,” encoding key historical moments, cultural values, and moral lessons into a group’s collective consciousness. This process allows ingroups to define themselves in contrast to outgroups by shaping conceptions of legitimacy, status, and social order.

What Is a Hostile Narrative?

A hostile narrative is a story used to legitimise violence against another person or group; to analyse a hostile narrative is to detect how processes of violence legitimisation feature in natural language. Drawing on Galtung’s concept of cultural violence, these narratives alter the “moral colour” of violent acts, transforming deeds that might otherwise be deemed unacceptable into justifiable or even necessary actions (Galtung, 1990). Typically, hostile narratives portray an ingroup as righteous and an outgroup as malevolent or dangerous, thus providing a rationale for exclusion, oppression, or direct violence (Bar-Tal, 2000; Kruglanski & Fishman, 2009).

By framing an outgroup as a threatening force, hostile narratives spark collective mobilisation and normalise aggression. As Presser (2018) notes, “war and other mass harms… are typically promoted by stories of a virtuous protagonist facing off against a malevolent other whose forceful overcoming is necessary for salvation.” Van Dijk (2014) similarly observes how stories can foster racism by suggesting that “we” are inherently superior to “them” or by implying that “they” fail to meet the norms valued by “our” social group.

The Meaning of Violence

Johan Galtung defines violence as “any avoidable insult to basic human needs, and, more generally, to sentient life of any kind, defined as that which is capable of suffering pain and enjoying wellbeing” (Galtung & Fischer, 2013a, p. 35). Galtung’s definition of violence broadens the common notion of violence beyond mere physical harm to more structural aspects thereby recognising that violence can be inflicted upon both individuals and collectives that have been rendered “nameless, faceless, [and] de-individualised” (Webel & Galtung, 2007, p. 23). Galtung’s theory aligns with Tajfel and Turner’s research on group identity formation. Tajfel and Turner’s work explains how “us” and “them” mentalities arise, with hostile narratives promoting the dehumanisation of targeted outgroups.

Three Types of Violence

Galtung (1990) conceptualises direct, structural, and cultural violence within a triangular framework:

Direct Violence is intentional acts of harm, whether physical or verbal, involving anything from a fist to nuclear weaponry (Galtung & Fischer, 2013a). Limiting direct violence aligns with what Galtung calls “negative peace,” or the absence of overt conflict (Galtung, 1969).

Structural Violence is harm arising from sociopolitical systems or policies that deprive groups of the basic needs and opportunities required to fulfil their potential (Webel & Galtung, 2007). A historical example is the 1967 Trade with Africa Act, which effectively enabled the slave trade. Countering structural violence seeks “positive peace,” in which unjust social frameworks are reformed (Galtung, 1969).

Cultural Violence comprises the ideological or cultural factors that legitimise both direct and structural violence (Galtung & Fischer, 2013c). It operates by framing the outgroup as inherently morally deficient or dangerous, often through one-sided histories or biased discourses.

Intention and Attributability

For Galtung, intention is crucial for distinguishing violent from non-violent actions: a deed must be purposefully committed by a specific actor (Galtung & Fischer, 2013c). Direct violence, like striking someone or launching a missile, is straightforward to attribute. Structural violence may involve malicious legislation or the deliberate neglect of harmful policies. Inaction, too, can be violent if it perpetuates avoidable harm (Galtung & Fischer, 2013b). In the domain of verbal aggression, words and stories themselves act as instruments of violence when deployed to cause psychological or social harm.

What Are Examples of a Hostile Narrative?

Hostile narratives emerge in different genres, which are characterised by the target outgroup. Although all serve to legitimise hostility, the selected target, ranging from an ethnic minority to an entire foreign government, defines the narrative’s themes and tactics:

Hate Speech (Target: Minority Groups)The hate speech genre of hostile narratives employs dehumanising language to single out groups defined by race, religion, ethnicity, or other characteristics. Examples include Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf (1925), which framed Jewish communities as existential threats to German identity, leading to genocidal policies (Hitler, 1925). Similarly, the Rwandan Genocide (1994) saw radio broadcasts label Tutsis as “cockroaches” (Des Forges, 1999).

Disinformation (Target: Democratic Organisations)Disinformation narratives seek to erode public faith in democratic institutions, such as parliaments, courts, or election commissions, by depicting them as corrupt or inept. Persistent disinformation can undermine the legitimacy of democratic processes, laying the groundwork for authoritarian regimes (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017).

Terrorist Narratives (Target: Government Organisations)Extremist groups often cast government agencies (e.g., military or police) as tyrannical forces, legitimising acts of terror as forms of “resistance.” In the aftermath of 9/11, propaganda from radical organisations portrayed government entities as valid targets for violent reprisals (Jackson, 2005).

Warfare Narratives (Target: Foreign Governments in the International Arena)In wartime propaganda, one nation’s government becomes the explicit target, with the adversary state depicted as a menacing or inferior power. Historical pamphlets, posters, and political speeches routinely emphasise the rival nation’s alleged barbarity, justifying military aggression by invoking national unity and survival (Lasswell, 1927).

Whether directed at minority groups or entire foreign governments, these narratives typically distort facts and exploit fear or prejudice to secure moral and emotional support for aggression.

How Do Hostile Narratives Legitimise Violence?

Hostile narratives legitimate violence by combining “elevation” of the ingroup with “othering” of the outgroup (Wodak & Meyer, 2009). In effect, ingroup elevation and outgroup othering create a Self-other gradient between each group. The steeper the Self-other gradient, the more legitimate violence against an outgroup becomes. When the ingroup is portrayed as inherently noble or heroic and the outgroup as villainous, group members may feel morally justified in endorsing or participating in harmful acts (Kelman & Hamilton, 1989). Social Identity Theory sheds further light on how group tensions escalate when the ingroup views itself as threatened or superior, while narratives reinforcing intergroup division make violence more acceptable as a defensive measure (Tajfel, 1982). Such narratives do not simply spark violence—they also sustain it by embedding justifications into broader political and cultural discussions.

The Role of Narrative Truth in Legitimising Violence

Narrative truth significantly contributes to the ingroup's imagined greatness and the outgroup's perceived malevolence. Unlike empirical truth, which relies on verifiable data, narrative truth is rooted in collective memory, ideology, and perception. It frames the ingroup as intrinsically virtuous or heroic, while portraying the outgroup as a fundamental hazard who harm the ingroup. Through repeated storytelling, historical reinterpretation, and ideological shaping, these hostile narratives become deeply entrenched, influencing both personal and collective behaviour. In extreme scenarios, this “us versus them” mindset normalises discrimination, exclusion, and violence.

Challenging the narrative truth of such deeply embedded beliefs can precipitate conflict, particularly when questioning the ingroup's cherished self-image. Attempts to correct misinformation or dispute one-sided histories may be interpreted as attacks on a community’s identity, sometimes leading to defensive aggression. In effect, countering a hostile narrative that extols the ingroup's imagined greatness can trigger a backlash, as the ingroup may cling even more tightly to its sense of virtue and superiority when it feels under scrutiny.

Conclusion

Narratives are not neutral; they influence how people perceive reality, justify actions, and reshape social dynamics. Hostile narratives are incredibly potent, casting outgroups as legitimate targets for harm. Understanding how these narratives work—and how violence can unfold in direct, structural, and cultural dimensions—is crucial to foster peace, encourage reconciliation, and reduce the appeal of extremist ideologies.

References

Akinsanya, C., & Bach, S. (2014). Narrative analysis: Exploring its uses and potentials. Nurse Researcher, 21(2), 14–19.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

Bar‐Tal, D. (2000). From intractable conflict through conflict resolution to reconciliation: Psychological analysis. Political Psychology, 21(2), 351-365.

Berger, Peter, and Thomas Luckmann. "The social construction of reality." Social theory re-wired. Routledge, 2016. 110-122.

Braddock, K. (2020). Weaponized words: The strategic role of persuasion in violent radicalization and counter-radicalization. Cambridge University Press.

Conway, M. (2016). Determining the role of the Internet in violent extremism and terrorism. In Violent extremism online (pp. 123-148). Routledge.

Des Forges, A. (1999). Leave none to tell the story. New York: Human Rights Watch.

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), 167–191.

Galtung, J. (1990). Cultural violence. Journal of Peace Research, 27(3), 291–305.

Galtung, J., & Fischer, D. (2013a). Johan Galtung: Pioneer of peace research (Vol. 1). Springer.

Galtung, J., & Fischer, D. (2013b). SpringerBriefs on pioneers in science and practice (Vol. 2). Springer.

Galtung, J., & Fischer, D. (2013c). SpringerBriefs on pioneers in science and practice (Vol. 5). Springer.

Hitler, A. (1925). Mein Kampf. Eher.

Hobbs, R. (2010). Digital and Media Literacy: A Plan of Action. A White Paper on the Digital and Media Literacy Recommendations of the Knight Commission on the Information Needs of Communities in a Democracy. Aspen Institute. 1 Dupont Circle NW Suite 700, Washington, DC 20036.

Jackson, R. (2005). Writing the war on terrorism: Language, politics and counter-terrorism. Manchester University Press.

Kelman, H. C., & Hamilton, V. L. (1989). Crimes of obedience: Toward a social psychology of authority and responsibility. Yale University Press.

Kruglanski, A. W., & Fishman, S. (2009). Psychological factors in terrorism and counterterrorism: Individual, group, and organizational levels of analysis. Social Issues and Policy Review, 3(1), 1-44.

Lasswell, H. D. (1927). Propaganda technique in the World War. K. Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Example reference; replace if needed.)

Martin, J. (2018). Neuroscience of language: Language, the brain, and cognition. [Example Publisher]. (Replace if needed.)

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1988). Narrative knowing and the human sciences. State University of New York Press.

Presser, L. (2018). Inside story: How narratives drive mass harm. University of California Press.

Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. SAGE. (Example reference; replace if needed.)

Tajfel, H. (1982). Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annual Review of Psychology, 33(1), 1–39. (Example reference; replace if needed.)

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

van Dijk, T. A. (1998). Ideology: A multidisciplinary approach. SAGE.

van Dijk, T. A. (2014). Discourse and knowledge: A sociocognitive approach. Cambridge University Press.

Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making. Council of Europe. (Example reference; replace if needed.)

Webel, C., & Galtung, J. (2007). Handbook of peace and conflict studies. Routledge.

Wertsch, J. V. (2002). Voices of collective remembering. Cambridge University Press. (Example reference; replace if needed.)

Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (Eds.). (2009). Methods of critical discourse analysis (2nd ed.). SAGE. (Example reference; replace if needed.)

Comments