What is the Methodological Framework for Analysing Hostile Narratives?

- Dr. Stephen Anning

- Nov 20, 2025

- 5 min read

The Methodological Framework for Analysing Hostile Narratives

The Differing Positions of Hate Speech Detection and Hostile Narrative Analysis

Hate speech research generally adopts a victim-focused perspective, assessing harm through the eyes of those targeted by speech. While this approach rightly centres on protecting individuals and communities from abuse, it is also highly subjective: what one person experiences as harmful, another might interpret as satire, irony, or even legitimate criticism. Such subjectivity makes it difficult to establish clear analytical boundaries, especially when trying to determine whether the speaker truly intended harm or was merely being provocative or sarcastic.

In contrast, the perpetrator-focused perspective taken in hostile narrative analysis begins by examining the speaker’s intent and the linguistic or narrative strategies used to legitimise hostility. This perspective does not excuse the behaviour but instead seeks to understand how language functions to justify harm. This perspective models language by the assertions an orator makes. For example, “All <social group> are scum” is an assertion dehumanising a social group as scum. The annotation of this assertion as hostile will have strong annotator agreement.

Although no approach is entirely free from interpretation, focusing on intent provides a more constrained and systematic framework for analysis, reducing disagreement about meaning and allowing clearer identification of when and how narratives legitimise violence.

Understanding the Theoretical Foundations of Hostile Narrative Analysis

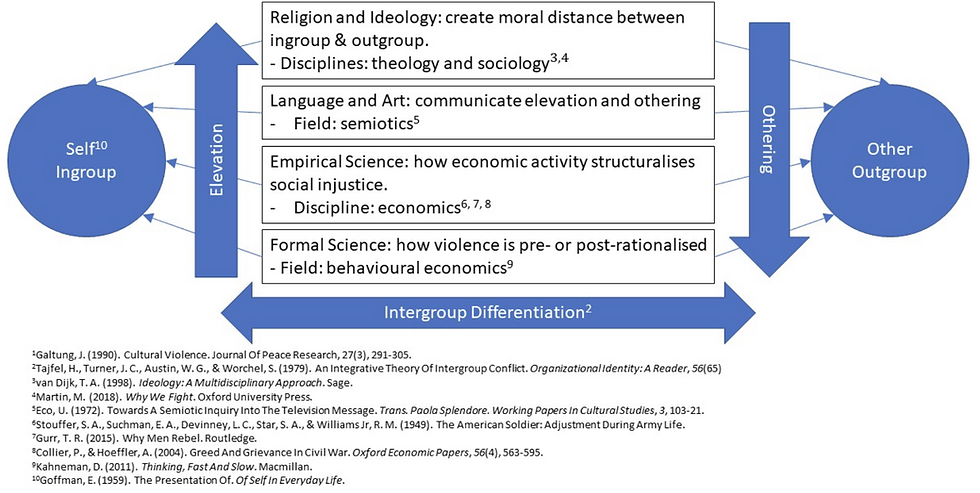

At its core, hostile narrative analysis is about understanding how language can be used to justify or legitimise harm. It builds on Johan Galtung’s theory of cultural violence (1990), which describes how aspets of culture - religion, ideology, language, art, and science - can make harmful actions seem acceptable or even necessary.

The framework begins with Galtung's idea of the “Self–Other gradient”. The Self-Other gradient describes how people, especially those speaking on behalf of a group, may elevate their own group (the Self or ingroup) while putting down another group (the Other or outgroup). The steeper this gradient—meaning the more one group is praised and the other demeaned—the easier it becomes to justify violence or harm towards the outgroup. For explanatory dialogues about hostile narratives, the Self-other gradient is expressed by the following hypothesis:

The steeper the Self-other gradient created by ingroup elevation and outgroup othering, the more legitimate violence against an outgroup becomes.

This hypothesis applies across different forms of hostility, whether racism, sexism, or homophobia. Each involves legitimising harm against a target group. The legitimisation of harm is expressed through open verbal abuse, through structural inequalities or discriminatory laws. Cultural violence helps explain how these forms of harm are justified and normalised. It shifts the focus from physical acts of violence to the underlying stories, beliefs, and ideas that make such acts possible.

Gatung’s Violence Triangle

Galtung defines violence broadly as any avoidable harm to human beings or other sentient life—anything that causes suffering or prevents wellbeing. As shown in the violence triangle, he describes three forms of violence:

Direct violence, such as physical or verbal attacks.

Structural violence, which arises from systems, institutions, or laws that disadvantage certain groups.

Cultural violence, which consists of the ideas, symbols, and beliefs that justify the first two.

Galtung’s model of violence

For example, if an orator uses language that dehumanises an outgroup—portraying them as inferior or dangerous—this cultural act can legitimise both structural discrimination and direct hostility. As Galtung’s model of violence shows, the instrument of harm, in this case, is not a weapon but a story, phrase, or metaphor.

Galtung also distinguishes between negative peace (reducing direct violence, such as war or assault) and positive peace (addressing the deeper structural inequalities that allow harm to persist). Hostile narrative analysis connects to both aims: by uncovering the stories and ideas that legitimise violence, it helps us to see where change is needed—both in what people say and in how societies are structured.

Culture and the Legitimisation of Violence

Cultural violence operates through different aspects of culture. Each domain—religion and ideology, language and art, and the sciences—can contribute to the Self–Other gradient in different ways.

Religion and Ideology provide moral frameworks. They tell people what is right or wrong, good or evil. Orators can use these frameworks to elevate their group as morally superior and to cast others as immoral or impure. For example, religious texts or ideological doctrines can be interpreted to justify intolerance or exclusion.

Language and Art communicate these moral distinctions through words, images, and symbols. In semiotics, language is understood as a system of signs that create meaning. When an orator contrasts “friends” and “enemies” or frames people as “good” versus “evil”, they are linguistically drawing the Self–Other boundary that supports cultural violence.

Empirical Science (such as economics) and Formal Science (such as logic and mathematics) can also play a role. Economic theories, for instance, have been used to justify inequality by naturalising status differences or suggesting some groups are more “productive” or “deserving” than others. Behavioural sciences show how people use mental shortcuts—heuristics—to make sense of social groups, which can lead to bias and discrimination. These rationalisations can become part of the cultural framework that legitimises harm.

Across all these cultural domains, the underlying mechanism is the same: by elevating the Self and diminishing the Other, a gradient of worth is created. The steeper the gradient, the more justifiable violence seems.

How Social Identity Theory Adds to This Framework

To understand how these cultural processes play out between groups, we can turn to Social Identity Theory, developed by Henri Tajfel and John Turner in the 1970s. They showed how people define themselves by the groups they belong to and how this belonging shapes their perceptions and behaviour. Tajfel and Turner describe groups as:

...a collection of individuals who perceive themselves to be members of the same social category, share some emotional involvement in a common definition of themselves and achieve some degree of social consensus about the evaluation of their group and their membership of it.

People naturally categorise themselves and others into groups—us and them. Once these categories form, individuals start favouring their own group (the ingroup) and discriminating against others (the outgroup), even when the differences are trivial. This process helps explain why people can quickly form strong group identities and justify unequal treatment of others.

Group prototypes, such as “the hero” or “the enemy”, become simplified symbols through which narratives about conflict are told. When an outgroup is dehumanised or portrayed as a threat, it becomes easier to rationalise harm towards them. As Galtung notes, when others are stripped of their individuality and humanity, the path is paved for any form of violence.

Social Identity Theory also explains how people seek positive distinctiveness—wanting their group to be seen as better or more deserving. This desire strengthens the Self–Other gradient and reinforces the legitimisation of harm.

Interestingly, research on hate speech detection often focuses on the othering aspect of hostility (the denigration of an outgroup) but tends to overlook ingroup elevation (the glorification of one’s own group). Hostile narrative analysis seeks to address this gap. By combining Galtung’s theory of cultural violence with social identity theory, the framework provides a richer, more human-centred understanding of how violence is justified in language.

In this way, hostile narrative analysis is not only a tool for studying speech but also a framework for dialogue—helping humans and machines alike to interpret the deeper social meanings behind harmful communication.

Comments