What is the Demand for Integrating Qualitative Research into AI systems for Policing Applications?

- Dr Stephen Anning

- Oct 20, 2025

- 9 min read

Introduction

The increasing adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) within UK policing highlights a profound need for “human-centric applications” that generate insights about people. While not explicitly stated, multiple police strategy and policy documents currently under consultation or in practice implicitly recognise this need. The premise underpinning human-centric AI is that it should synthesise quantitative methods, which enable large-scale data processes driving predictive models, with deeper, more interpretive, and context-rich methods, often referred to as qualitative research.

This analysis examines the demand for integrating qualitative approaches into AI-enabled policing systems. It does so by evaluating relevant police documents – including the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) Covenant for Using Artificial Intelligence in Policing, the College of Policing’s guidance on Data-Driven Technologies and Data Ethics, and other policy or strategic papers – to verify where, how and why such qualitative methods are needed. The analysis distinguishes between three main uses of qualitative research in AI:

To assess AI applications themselves (e.g. auditing algorithmic outputs through interviews, focus groups, user acceptance evaluations).

To assess public attitudes (e.g. co-design sessions, community forums, stakeholder engagement to understand trust in AI).

To integrate qualitative research within intelligence analysis applications to interpret human behaviour in ways that purely quantitative metrics may miss.

Ultimately, reliance on numbers alone can overlook vital human factors, such as cultural context, nuanced patterns of behaviour, and community sentiment. As policing in Britain moves further into the digital age, the synergy between qualitative and quantitative is increasingly essential to maintaining public trust, ensuring meaningful community engagement, and evolving truly “human-centric” intelligence tools that do more than simply crunch data.

AI in Policing and the Role of Human-Centricity

The AI Covenant and Human-Centric Foundations

The Covenant for Using Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Policing states that forces should act with maximum transparency, explainability, and responsibility when deploying AI. One of its central themes is that “public confidence” remains paramount, an objective which requires policing to engage with communities about AI’s capabilities, risks, and potential biases. In referencing the calls for “community representation” and “independent assessors,” the Covenant implicitly highlights a requirement for more deliberative, qualitative approaches – such as involving public panels, user testimonies, and ethnographic investigations – to ensure that “the fear of unintended consequences and impingement of civil liberties, deservedly or not, is associated with policing’s use of AI” is addressed through open dialogue.

While this call for open dialogue does not name “qualitative research methods,” emphasising transparency, accountability, and stakeholder engagement is precisely where focus groups, interviews, and in-depth case analyses shine. Such activities help to understand not just whether an AI system may be legally compliant but also how it intersects with people’s lived experiences, cultural perceptions, and shifting ethical norms. Engaging with the public’s lived experiences, cultural perceptions and shifting ethical norms is how governments can earn the public’s trust for an AI-enabled government.

Data-Driven Technologies APP: Community and Stakeholder Input

In the College of Policing’s Data-driven Technologies Authorised Professional Practice (APP) consultation, “engagement with partners and the public” is repeated as part of decision-making about adopting new technologies. The document states, “Project leads should engage widely with community leaders and interested groups at an early stage, particularly in cases which may be contentious.” This underscores that, to gauge potential harms or benefits, qualitative research – such as structured interviews with vulnerable communities, workshops with partner agencies, and direct consultation with local residents – provides rich insights that raw data can rarely capture.

Likewise, the reference to “stakeholder engagement and environmental scanning” within the same document indicates an approach in which policing can systematically gather community sentiment or apprehension, calibrate those insights, and adapt the technology solution accordingly. Though broad terms like “engagement” or “environmental scanning” do not explicitly spell out “qualitative research,” the intent is there: an informed, two-way conversation beyond the purely technical aspects of artificial intelligence.

Data Ethics APP: Understanding and Evaluating Impact

The College of Policing’s Data Ethics APP aligns closely with the principle that policing’s data collection, storage, and use must be grounded in ethical considerations. Among other data ethics principles, it stresses the importance of evaluating how data processes might “undermine the dignity of individuals and groups” and how to determine “what steps could be taken to reduce any negative impact.”

To genuinely assess dignity, vulnerability, or disparate outcomes for marginalised populations, policing must go beyond quantitative accuracy metrics and adopt robust qualitative measures. Such qualitative measures for understanding the dignity, vulnerability or disparate outcomes for marginalised populations include focus groups with affected communities, semi-structured interviews with front-line officers, or scenario-based exercises that examine how humans interpret AI recommendations in complex real-world conditions.

Differentiating Core Qualitative Needs in AI-Enabled Policing

Because “human-centric applications” of AI in policing encompass multiple domains, it is helpful to break down the integration of qualitative approaches according to three distinct activities: (1) assessing AI systems, (2) assessing public attitudes, and (3) integrating qualitative research within intelligence analysis.

Using Qualitative Methods to Assess AI Applications

One obvious reason for blending qualitative methods into AI systems is to evaluate the technology’s performance and implications:

Algorithmic Audits: While purely technical audits measure bias or drift, combining them with qualitative user testing (e.g. interviews with operational officers, observation sessions of real-world usage) reveals why an AI system might yield false alerts or cause confusion. Such insights can reorient design decisions for better real-world compatibility.

User Acceptance and Interpretability: The Data Ethics APP emphasises “robust evidence” to determine whether a procedure meets public and professional needs. Observational studies or officer feedback sessions shed light on how humans understand an AI tool’s recommended actions and whether reliance on AI might overshadow professional judgment.

Adaptation Over Time: As one of the policing and AI reports states, policing is “permanently fighting fires,” meaning demands change rapidly. Qualitative research, such as scenario testing or multi-agency pilot focus groups, can reveal how an AI system must adapt. Without that, the system remains static and inattentive to emergent complexities.

Using Qualitative Methods to Assess Public Attitudes

Public trust is a central theme across all of these documents. The “fear of unintended consequences” or “impingement of civil liberties” arises if local communities feel they have no voice in shaping AI usage. Hence, the Data-driven Technologies APP specifically recommends “community impact assessments,” “public communications,” and “engagement with ethics committees.”

Public Deliberation and Workshops: Instead of surveying thousands of residents for superficial opinions, community roundtables or interactive workshops can highlight nuanced concerns around privacy, fairness, or how AI might exacerbate existing inequalities.

Citizens’ Panels: Panels or forums, drawn from a cross-section of local populations, can deliberate on AI scenarios and offer grounded feedback that a simpler yes/no poll could miss. For instance, panels might weigh in on the appropriateness of facial recognition in high-traffic public spaces, balancing crime reduction claims against potential “chilling effects.”

Ongoing Qualitative Monitoring: Trust is dynamic, so attitudes can shift, especially if an incident sparks controversy over algorithmic bias. Regular focus groups or public Q&A sessions can help police leaders track the evolution of trust or distrust, enabling agile responses.

Integrating Qualitative Research in Intelligence Analysis

Finally, the primary focus of this research: can policing embed qualitative research into intelligence analysis for a richer, more “human-centric” understanding of suspects, victims, and entire communities? The short answer is “yes”. Policing already uses qualitative research in its intelligence research, the challenge now is to integrate these existing and proven qualitative approaches into AI-enabled systems.

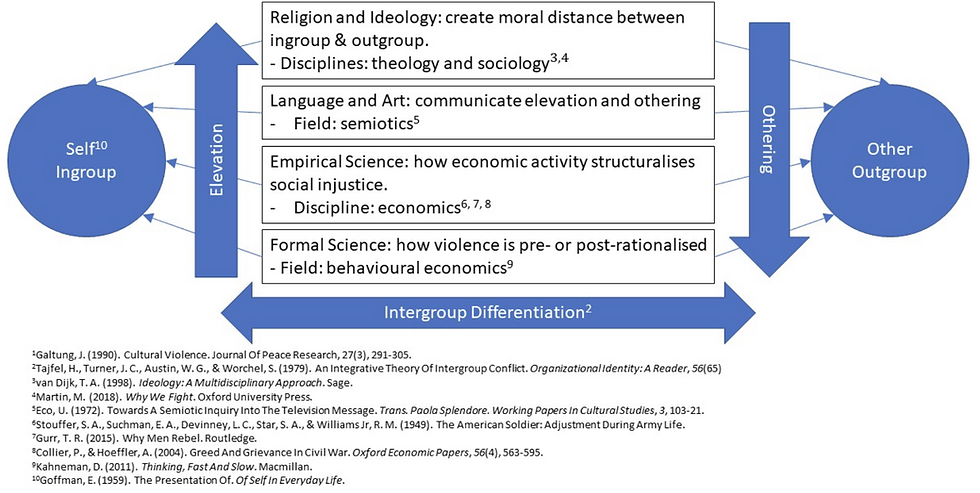

Ethnographic Insights: For crimes such as gang-related violence or hate incidents, purely quantitative data (criminal history, location data, social media footprints) can overlook intangible factors like group identity, local codes of honour, or hidden cultural norms. Embedding ethnographic intelligence – for instance, collecting stories from support services, community advocates, or youth workers – can help interpret data signals more accurately.

Narrative Analysis: As recommended in the Data Ethics APP, applying “interpretive frameworks” to textual or discursive data often reveals how real human context influences risk. For example, AI might automatically flag a reoffending risk, but a companion piece of qualitative research might uncover a suspect’s personal motivations and potential for targeted intervention.

Collaborative Decision-Making: The National Policing Digital Strategy warns that technology “cannot be an end in itself” and must be integrated with deeper knowledge systems. Qualitative inputs, facilitated by specially trained intelligence analysts, can ensure that AI in policing remains sensitive to lived realities – whether tackling radicalisation, domestic abuse, or youth criminal exploitation – in ways that raw pattern recognition cannot fully grasp.

Evidence of Demand in Policing Documents

The five principal documents contain repeated evidence of an emerging demand for qualitative approaches:

Covenant for Using AI in Policing: This covenant prioritises transparent, fair, and explainable AI. It states, “Forces should ensure the public is aware of AI uses… including the known limitations of the training data used.” Achieving this public awareness in practice inevitably requires deeper conversation and iterative feedback with communities, which is a quintessentially qualitative undertaking.

Data-driven Technologies APP: Calls for meaningful community and stakeholder engagement, emphasising the need for “community impact assessments (CIA), equality impact assessments (EIA) and human rights impact assessments (HRIA)” that incorporate broad or in-depth consultation.

Data Ethics APP: This authorised professional practice emphasises “Respect and Dignity,” “Fairness and Impartiality,” and “Transparency and Accountability,” linking them with explicit questions about potential adverse outcomes and the role of communities in shaping decisions. The APP suggests that qualitative methods are crucial for determining whether data processes inadvertently harm individuals and groups.

National Policing Digital Strategy (2020–2030): reiterates that harnessing digital technology to create public value is not only a technical challenge but also a social one: “We can make huge gains in productivity by turning to technology… but we will harness the power of digital technologies and behaviours to identify risk of harm and protect the vulnerable.” Co-design with those communities ensures that the technology hits the mark.

Policing and AI (Feb 2025): – Stresses that policing is “an overwhelmingly reactive business,” often lacking the impetus to consider future implications or broader trust issues. Qualitative engagement is presented as vital to bridging that gap, with suggestions that “police leaders who want to innovate” need robust feedback from those experiencing policing on the ground.

Together, these documents form a mosaic of demand. They call for the policing community to adopt and champion approaches that let the voices of the public, officers, staff, and experts shape AI’s design, deployment, and refinement.

Next Steps and Recommendations

Building Internal Capacity for Qualitative Evaluation

Forces should invest in upskilling an expert cadre of officers with the skills required to integrated their expertise with AI. These officers already have expertise in social research methods, such as conducting structured interviews, running community forums, facilitating focus groups, and interpreting textual or narrative data. This skillset must be valued and integrated at the same level as data science roles, ensuring the workforce can robustly evaluate AI systems.

Formalising Stakeholder Engagement Requirements

In line with the Data-driven Technologies APP, forces might institute a mandatory stakeholder engagement phase for any significant AI deployment. This could include:

Public deliberation for higher-risk applications (e.g. live facial recognition)

Qualitative assessments for lower-level changes (e.g. chatbots in call centres)

Embedding Qualitative Methods in Governance

Whether at local force ethics committees or the national Data & Analytics Board, there should be explicit reference to a “qualitative evidence stream.” Each AI project, from pilot to rollout, should produce user-based and community-based insights, not just numeric performance indicators.

Experimenting with Co-Design in Intelligence Analysis

Teams responsible for intelligence-led applications (e.g. predictive analytics) could partner with civil society groups, academics, or local service providers to shape model design using in-person dialogues. Workshops might explore how data correlates with real-world experiences and whether different contexts complicate the model’s assumptions.

Transparency and Iterative Improvement

Policing bodies can publish summaries of qualitative findings, highlighting improvements made to AI solutions following that feedback. This approach fosters trust. Particularly with large-scale or sensitive deployments, publicly sharing how the force integrated local concerns and ethical deliberations encourages accountability.

Conclusion

The evidence across NPCC statements, College of Policing APPs, national strategies, and emerging best practices all point to the same conclusion: for AI to be legitimately “human-centric,” policing must actively integrate qualitative research as a standard, not an afterthought. Addressing ethical, social, and cultural factors ensures technology is truly in service of the communities it aims to protect. By seizing these opportunities for qualitative inclusion, British policing can pioneer an era of responsible AI that balances innovation with humanity.

AI-driven policing applications hold immense promise for improving efficiency (e.g., robotic process automation for redaction or data entry) and enhancing effectiveness (e.g., scanning large data sets to detect hotspots, perform advanced risk assessments, or accelerate investigations). Yet, as multiple police documents reflect, there is a clear and growing demand for more holistic, human-centric methods that account for societal, ethical, and personal variables to maintain a strong relationship between the public and the police.

Qualitative research stands at the centre of maintaining a strong relationship between the public and the policy. Qualitative research provides a vital conduit through which the nuanced voices of communities, officers, and broader stakeholders can shape the adoption of AI technology. Through robust public engagement, multi-stakeholder forums, user testing, and ethnographic or narrative analyses, policing can avoid pitfalls of algorithmic bias, misinterpretation, and public distrust.

In short, purely quantitative data can reveal what is happening, but not always why or how it impacts humans. By blending interpretive, context-rich insights into every stage of AI adoption, from the design of call-handling bots to the strategic calibration of facial recognition software, forces can develop systems worthy of public confidence. The “overreliance on quantitative methods” that misses “the more qualitative aspects of humanity” can be corrected through inclusive dialogue and a structured infusion of qualitative practice.

References

College of Policing (2025) Data-driven technologies

National Police Chiefs’ Council (2023) Covenant for Using Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Policing

College of Policing (2025) Data ethics

Comments